RIP Chacaltaya Bolivia, World's highest ski area

Throwback Thursday is a good day to remember Chacaltaya, formerly the World’s highest ski area.

And say bye bye Bolivian skiing, because Chacaltaya is no more. The once extensive glacier that topped 5,400m sadly melted into memory over a decade ago.

That was several years early than climate change predictions had forecast only 20 years before.

So if you think projections for losing our entire lift-accessed skiing in Australia are far-fetched ,just ask the snow sport aficionados in Bolivia, which used to be the 7th country with a ski field in the Southern Hemisphere.

Back in the 1940s the South American Ski Championships at Chacaltaya attracted over 2,000 spectators to the one-tow field on the glacier at 5,396m – that’s the Argentinian team posing proudly here.

There was a decent 2km long ski run in those days, and a season that lasted December to March. This is the “Bolivian winter”, the wetter season in the Altiplano high plateau there, despite it technically being summer in the Southern Hemisphere.

Snowfalls were often quite heavy, and certainly more than enough to replenish the glacier through the arid season and hold up on sunny tropical days.

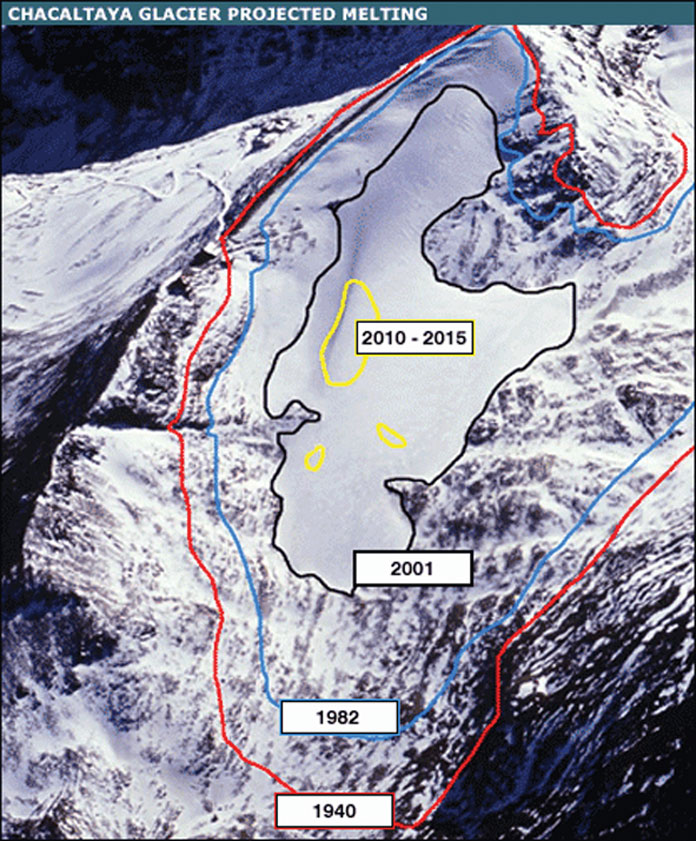

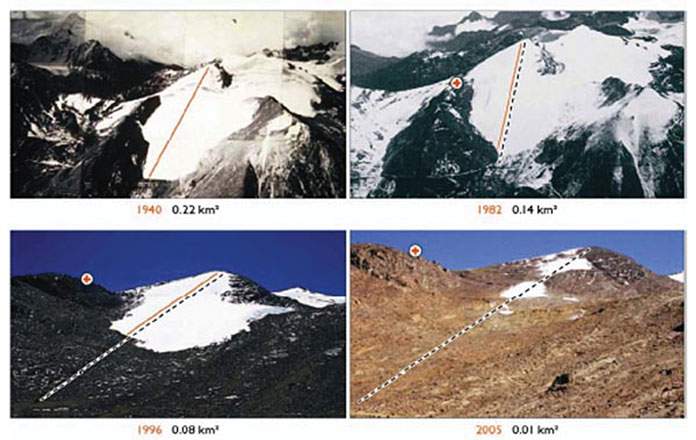

Then the glacier started retreating. People got worried. In the 1980’s the Club Andino Boliviano who ran Chacaltaya had to shorten the lift. Studies were done and published, including the one shown below here, with a graph predicting the permanent ice would melt away by 2015.

That proved over optimistic. Lift accessed skiing stopped over a decade ago as the glacier completely disappeared in 2008.

Now there are still snowfalls, sometimes quite decent ones, but there is no base beneath to allow a lift to work.

In our 2007 feature on Chacaltaya contributors Paul Tansley and Ben Fuller managed to hike a few short laps on what there was.

“We managed three walk ups before the lack of oxygen sent us scurrying back to the lodge in search of coca tea and a good lie down” Tansley reported.

“To get an idea of the run at Chacaltaya, imagine end of season Front Valley at Perisher, with just you and a mate having the place to yourselves, but with spectacular views across the Andes to Chile and Peru – combined with the inability to breath.”

That’s a far cry from the 40s and 50s, when (with the help of some recently arrived German immigrants, Nazi Hunters afficionados will know more about that), skiing got popular.

According to a 2016 study by a team from Manchester University published in The Cryosphere, Bolivia’s glaciers shrank by a frightening 43.1% between 1986 and 2014. Says team lead author Simon Cook “Our mapping from satellite imagery reveals an overall areal shrinkage of 228.1 ± 22.8 km2 (43.1 %) across the Bolivian Cordillera Oriental between 1986 and 2014.”

Of course that’s bad enough for local skiers and boarders. But far worse is the shrinkage of the higher, larger glaciers that provide dry season snow melt flow for the rivers supplying water to the World’s highest capital city, La Paz, and adjacent Lo Alto up on the bleak altiplano high plateau.

Lo Alto is also home to the international airport. Fly in here, or indeed fly anywhere along the tropical Andes up to Colombia, and you can see the evidence of retreating glaciers.

The population of the greater urban area is well over 2 million, most of whom live in poverty, especially in desolate Lo Alto.

The city is only an hour drive from Mount Chacaltaya. Heavy use of diesel engines and resultant pollution exacerbates the problems. Even when it does snow nowadays the snow can be covered in slimy grit.

This combination of local and global factors is accelerating the retreat of the glaciers, adding up to a disaster that dwarfs the loss of skiing in the scale of things.

Coincidentally, the latest upate from the American Ski Industry Association lobbed in this morning, right on topic.

“Spring snowpack in the northern hemisphere has already been reduced by a million square miles and in Park City, the host of the 2002 Winter Olympics and home to SIA, snowpack could be reduced to zero by 2100” says SIA President Nick Sargent.

They are getting on with doing something about it too, launching ClimateUnited, a platform to unite the winter outdoor industry around meaningful climate action. Check more on that on the link.

In the middle of another low snow October down under, as even out on the Main Range the snowpack is disappearing fast, we shouldn’t need reminding how the fate of our favourite recreation and entire industry is intimately entwined with that of the planet.

Thredbo’s snowmaking breakdown in August peak season this 2020 winter showed starkly how dependent Australian resort skiing already is on snowmaking. Even that won’t keep up with the changing climate the way things are going.

The loss of Chacaltaya is one stone dead canary in the coalmine you could say, mangling a few metaphors..